Origins

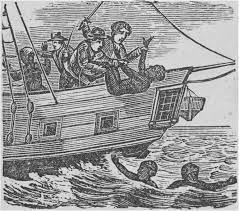

We know the origins of ‘nigger’, now routinely and rightly relegated to the “n-word” first in the United States and then elsewhere in recognition of its offensiveness and history in relation to people of African heritage, especially in America, but also elsewhere, not least the UK from where it originated before being turned into “the nuclear bomb of racial epithets”, as Kennedy termed it, in America. He is not the first to write about it. As he points out, a number of authors have written about it and have referenced the fact that the British recipients of the first twenty or so Africans trafficked against their will in 1619 to Jamestown, Virginia, the first British settlement in North America, founded just twelve years before, labelled them ‘negars’. One of the traffickers themselves who seized them from a Portuguese slave ship, as the British state was encouraging pirates to raid Spanish and Portuguese ships of any “cargo” at the time, a British pirate by the name of John Colyn Jope, wrote separately of “20. and Odd Negroes”.2

Lack of irony, plenty of contagion

What struck me as odd in 2003, and still does now, was that Kennedy liberally used the words “black” and “blacks” to refer to African Americans, of which he is one, and none of the questions posed to him, nor his answers, touched on the irony of “nigger” being a racial slur for anyone of African heritage both within and without the United States, while the English word ‘black’ that underlies it and gave birth to it along with, arguably, the Spanish word ‘negro’/‘negra’ is somehow accepted by so many African Americans in the United States. Perhaps it’s an American thing. The problem is, for better or for worse, through the sheer power and reach of American broadcasting, distribution and marketing, American cultural ‘norms’ are infectious and far-reaching and this way of thinking has reached and infected just about everywhere in the world, including the United Kingdom.

‘Black everything’ has become an industry of its own, with its head office in America

‘Black man’, ‘black woman’, ‘black boy’, ‘black girl’, ‘black person’, ‘black people’, ‘black kids’ to label people. Then derived from that, we have inanimate objects so-named, chiefly ’black music’, ‘music of ‘black’ origin’ (When you actually think about it, what does that really mean?), ‘black history’, ‘black studies’, ’black businesses’, ‘the black dollar/pound’. For these inanimate objects, I advocate this word: ‘Afroic’, or else ‘African’ or ‘African diasporic’. If you’re concerned about differentiating continental African from diasporic then saying ‘continental African’ resolves that.

Six key questions

Over the decades since I first questioned ‘black’ in 1992, I’ve come to narrow the issue down to these six questions:

Why has the term ‘black’ persisted as a term of reference to the complexion of people of African heritage, whose complexions are and always have been various shades of brown?

Why is this term not applied to people of south Asian heritage, particularly Madras Indians and Sri Lankans, many of whom have complexions just as brown as, and in many cases, far deeper brown than many people of African heritage?

What is it that makes so many people of African heritage see a false and primitive Eurocentric representation of their skin complexion as an appropriate way to define their entire being and to refer to them?

Why do they accept the routine and systematic definition of them as being the opposite of European based on this false depiction of skin complexion?

Why do they complain about racism while so readily accepting this label, which was never intended to be anything other than derogatory or pejorative in reference to people of African heritage by those Europeans trafficking them from Africa across to the Americas and north to Europe, and underlies the very racism they complain about?

Why is that they appear not to question why they accept being singled out for skin-labelling that disrespects and ignores their ancestral and geo-cultural heritage?

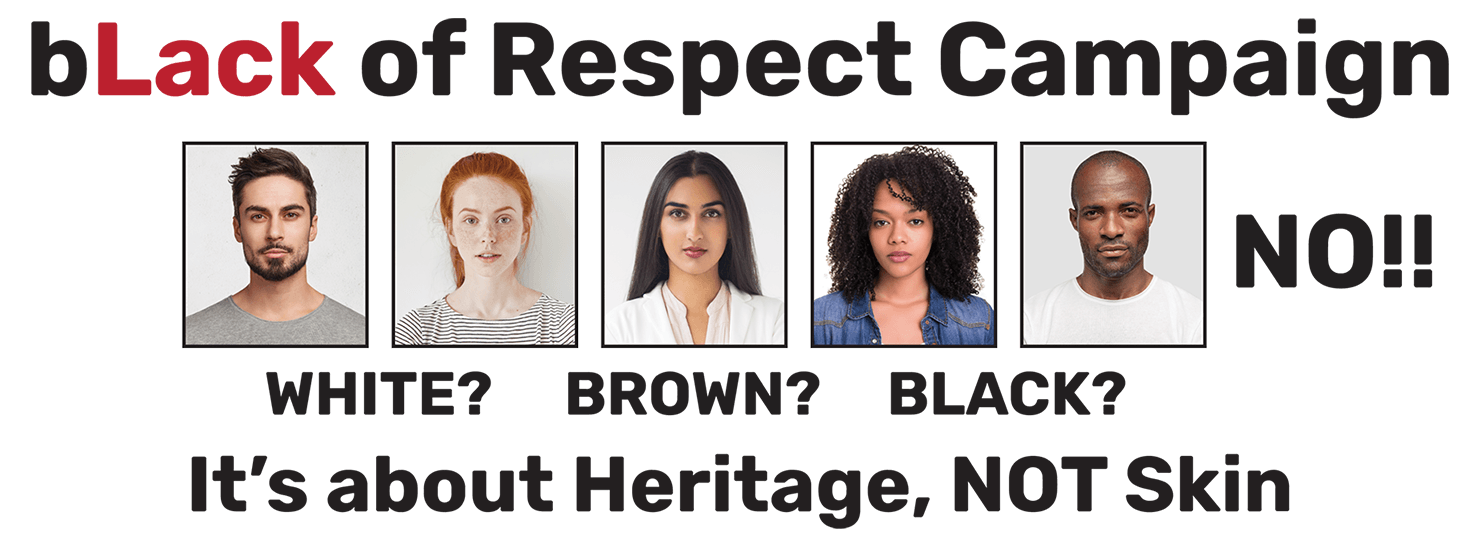

‘Black’, over-simplistic thinking, and its thoughtless importation into British medical treatment guidelines

And I was galvanised into turning these questions into a campaign during my medical work when a pharmaceutical rep came to my consulting room to market an anti-hypertensive drug in 2008 and presented me with a mouse mat with an imprint of the then 2006 UK ‘NICE guidelines’ as a ‘freebie’. These guidelines, printed and also posted online advised the giving of a particular drug as first choice for people aged less than 55 years, “or black”. When I questioned, as a fellow medical professional, the lead author of the guidelines as to the choice of terminology, the answer he gave was far from satisfactory. I took this further within the profession and then decided to campaign more widely against the routine and widespread use of ‘black’ as a term for people of African heritage, eventually giving the campaign its name, the bLack of Respect campaign, in 2011.

British institutional ignorance and wilful blindness

When I put the six aforementioned questions to people of African heritage in the UK, the vast majority immediately get the problem, others are vague and sketchy in their answers, and some simply don’t get it. Worse, when these questions have been put to British agencies supposedly there to fight racism in the UK, such as The Runnymede Trust, The Equality and Human Rights Commission, Kick racism Out of Football, and the National Black Police Association, the response has either been embarrassment, bemusement or, in some cases, deafening silence. The level of obtuseness and blindness on these fundamental questions is astonishing, yet these are some of the British organisations claiming to be at the vanguard of the fight against British “institutional racism” and the fight for ‘equality’. Again, astonishing.

Past drivers of ‘black’ and how ‘black’ gave way to ‘African American’

I am not the only person who has been given cause to question it or write an essay, monograph, tract or book about it. Kwesi Tsri, in his book “Africans are not black: the case for conceptual liberation”, published in 2016 and 2018, presents a well-argued case, with plenty of evidence to show that the central question as to the justification of ‘black’ or ‘Black’ or ‘blacks’ or ‘Blacks’ to refer routinely to people of African heritage has been on the minds of many.3

In truth, there is in modern times no ethical, moral, logical, intellectually thought-through, or other justification for the persistence with this.

In terms of political justification, over half a century ago ‘black’ served an important purpose with courage and excellence in the USA. In the America of the 1960s, “Black Power” served to state clearly and unequivocally to the rest of America that people of African heritage there were no longer ashamed of their complexions and their hair and were no longer going to accept being called ‘negroes’.

That caught the headlines and had wash-over effects elsewhere in the world, not least on what was then, and still is, a relatively small population of people of African heritage in the UK.

But the time of the Black Power movement has long since passed.

When Jesse Jackson successfully argued for ‘African American’ to enter the American lexicon in place of ‘black’ in December 1988, he gave voice to a growing clamour for recognition of and respect for and the statement proudly of the African heritage of those people who were the descendants of people forcibly displaced from that continent of Africa and enslaved first on ships and then on the land of what is now the United States of America, rather than them just being called “black people” or “black Americans”.…and he was right. As it turns out, the first known use of ‘African American’ extends as far back as 1782 in the pamphlet “Sermon on the capture of Lord Cornwallis”, which was re-discovered as recently as 2016.4,5 So common sense on this existed over 230 years ago, yet lay dormant along with the document, under the mists of time and American culture until it was revived in the 1970s and championed in the late 1980s by Reverend Jackson.

Regression, ‘Black Lives Matter’, victimhood and the American marketing machine

Sadly, there has been a modicum of regression and push-back on this in America. It’s not uncommon to hear ‘black’ used interchangeably with ‘African American’, often by the same person in the same breath. I find this unfortunate, but not surprising in a society built on division and a culture that places so much emphasis on abbreviation, brevity and packaging.

The rise in recent years of the "Black Lives Matter (BLM)" movement, founded in the US by thee women of African heritage, is a product of America's toxic, violent, skin-obsessed culture that has never got over the poison of the enslavement of Africans and their descendants, and the war it took to “free” them. I deliberately place “free” in inverted commas because slavery in the commonly understood sense that took place in America's South and Deep South has merely been replaced by other forms, not just economic, legislative and policing (so-called 'law enforcement' methods), but mental, all over America. What's more, however well marketed it is (and it is, because America has always been good at that), it is, in my view, retrograde and misguided. No-one has a "black life": people may have a black mood or black outlook in the sense of depression and pessimism, but that is not what the founders of BLM mean. With BLM, “black” has come to equate to, not pride, but victimhood.

The British version of ‘blackery’ and its entanglement with state-sanctioned, industrial-scale brainwashing and ‘divide and rule’

Long before the arrival of BLM in America, ‘black’ over here in the UK has become nothing more than an amalgam of four things:

1) misrepresentation of skin colour,

2) the notion that it is some kind of disease, affliction or something to be ashamed of,

3) the experience of victimhood,

4) all while trying to suppress or deny any connection with the African continent, especially among those descended from Africa via the Caribbean

This has been the direct result of:

(a) the exercise of British divide and rule by elites on both sides of the political spectrum in central and local government, including education departments, pitting those of African ancestry from the Caribbean (African-Caribbean people, formerly called “West Indians” by the British), who were in the majority between 1950 and 2000, and those of direct continental African ancestry, who were in the minority during this period, and

(b) elites on the left of the political spectrum paying lip service to community relations and social mobility while tolerating and reinforcing (whether deliberately or not) ignorance, low achievement and low self-esteem

(c) reinforcement of this notion of two “unrelated ‘black’ communities” by way of dramas and ‘popular culture’ on mainstream British television, radio and now the internet and social media

The likes of the BBC, The Guardian newspaper, The Equality and Human Rights Commission, The Runnymede Trust, and above all, the Office for National Statistics (ONS), an executive branch of British Government for decades that puts out the Census, reinforces victimhood and are happy with eternal victims: they want an endless parade of people of African heritage to come on TV and radio not to talk about being discriminated against because of their African heritage but because they are "black", or to reduce the discrimination down to being "because of the colour of their skin”.

So, where has ‘black’ got us collectively as a population in the UK?

I would argue, not very far.

Social policy, schooling and the social ladder

On the whole, we are at the foot of the social ladder. But not all of us; there are many success stories, but they tend to be individual rather than communal. Attempts to found schools for disadvantaged children of African heritage has met repeatedly with obstacles, usually taking the form of funding being conditional on allowing in children from other communities. The left of the British political spectrum is obsessed with the fear that such schools will amount to US-style segregation and they’d rather have the status quo here than allow the experiment to be at least tried to see if this is true or whether instead we will have a collectively successful community within and contributing to wider British society much as British Indians do.

The Office For National Statistics

Meanwhile, the ONS has insisted on trying to keep us divided as “black African”, “black Caribbean”, “black British” and “black other”, claiming they need this for statistical purposes and “to avoid confusion” and “improve services to disadvantaged communities”.

To this and the policy on schooling I ask these two related questions:

Where is the evidence that this helped children and adults of African heritage in Britain in 70 years?

What has the Equal Opportunities Act of 1976 actually done for us in 45 years while using these colour labels?

Consistently, including in the latest report on race in Britain, commissioned by the current Prime Minister Boris Johnson and published on 13th March 2021,6 so-called “black Caribbean” children have been singled out as being the lowest educational achievers, as though this is some static situation when the opposite is true, and more importantly, while preferring to ignore the fact that these ethnic distinctions are increasingly meaningless in Britain as increasing numbers of younger people of African heritage are descendants of intermarriage between so-called “black African” and “black Caribbean” populations. The notion that these ‘two populations’ are still separate and distinct is a falsehood and to try to perpetuate it has, self-evidently, more to do with continuing to divide, confuse and rule than assisting these communities, and nothing to do with “avoiding confusion” as claimed.

Lip service and chronic tokenism

Between 1948 (the first year of the so-called Windrush generation) and 1981, British racism took two reactionary forms against people of African heritage - one anti-cultural, against what was then a very visible and predominant African-Caribbean culture labelled “West Indian” and one which ridiculed and despised our skin complexions with the label ‘black’ and its derivatives ‘nig-nog’, ‘wog’, ‘coon’, ‘spade’ and the hypocritically ‘polite’ ‘coloured’. In the years since 1981, under the guise of ‘integration’ and ‘assimilation’ as first and second generation of British-born people of African heritage have grown up, we have unwittingly allowed British racism toward people of African heritage to be trivialised and reduced to nothing more than the visual only. Instead of the historical and current disrespect for African ancestral heritage as being inferior to European (and other heritages), analysing this in depth and remedying it, the content of the national discourse has dwindled to nothing more than that of “colour of skin” and ‘ “not enough black faces on television” or in organisations because of “institutional racism” and “unconscious bias” ’. Meanwhile, the nature of and the discourse on, anti-south Asian racism has remained steadfastly cultural, with, arguably, a more intellectual and respectful approach to solutions. Certainly, in terms of societal position, be that in terms of economics, or being in positions of influence in society - corporate partnership positions, editorial and producer positions (i.e. positions behind the camera, not just being placed in front of the camera to read the news or weather), hosting prestigious radio programmes on the BBC’s flagship Radio 4 rather than just lighthearted programmes on BBC local and regional radio, Parliamentary select committee chairmanships, judicial appointments and, above all, entrepreneurship, they are well ahead of people of African heritage, although we are at long last catching onto the merits of the latter.

Do south (and indeed south-east and east) Asians not experience racism in the UK?

Of course they do. But it takes a different form. For decades, any racist insulting someone of south Asian heritage has only had the imagination to label them by an abbreviated form of the south Asian country Pakistan. Even if, granted, this abbreviation is highly insulting to many south Asians, particularly to Indians, I would argue that this owes more to the ignorance of the racist as to the painful cultural and religious history of what was the ‘Indian subcontinent’, the trauma of partition in 1947 and the legacy of this to the present day. The fact is that, in the case of south Asians, continental-born or displaced, descendants of indentured labourers or not, whether wearing traditional attire or not, the vast majority of them wear their heritage on their sleeve and with pride. And they have shown that just as with ‘African American’ they can be British Asian - British by nationality, Asian by heritage. More importantly, they respect their heritage. A contingent of them has only taken ‘brown’ as “shorthand” for south Asian, not because it has been relentlessly imposed on them after it was first coined for Arab, Persian and south Asian races by a European in the 17th century, but almost as a lighthearted joke because (a) people of African heritage left open that obvious vacancy, (b) because it lacks all the negative, denigratory, pernicious qualities and historical baggage that ‘black’ has and instead has an air of clean respectability about it, and (c) it places them at distance from, and indeed is generally perceived to be, above, people of African heritage in the colour-based social pecking order. In the UK for a brief period, from the late 1960s up to about 1980, and in the wake of that brief period of headline-grabbing pride that was Black Power, some south Asians stood under the same umbrella of ‘black’ as people of African heritage, but as the years rolled on, so they began to distance themselves and coalesce around their own identities, underscored by their continental ancestry.

Yes, their history is different, but that doesn’t mean we cannot learn from them.

I argue the following:

A person saying: “You’re a black person”, no matter how ‘liberal’ or left-wing they are, or how anti-racist they intend to be, fails to convey respect. At best, the term conveys the fact that they are expressing a racial epithet that we have deluded ourselves is fine, and we have told them we don’t mind and we actually want them to call us that. At worst, it conveys a pity and condescension for what we have experienced - racism, oppression, violence, dispossession, rootlessness and disadvantage. The casual “He’s a black guy” and “She’s a black girl” don’t convey respect either. Both convey a casual familiarity, indeed an overfamiliarity, and the latter combines that with a degree of misogyny, all of which we can do without. And “I’m a black person”, no matter how proudly or emotively we think we are telling people, far from conveying self-respect, connotes victimhood, rootlessness, disadvantage and low self-esteem.

Any terminology that forces a person to say: “I don’t mind being called such and such.” tells you two things:

1) It has been imposed

2) There is something wrong with it

Those of us who continue to wallow in ‘black’ as a “badge of honour” are inadvertently giving legitimacy to a label that has been routinely used to denigrate and dehumanise us in a way that no other population on earth suffers, either by using it as the prefix within an insult - the British method of choice, e.g. ‘black bastard’ and, less commonly nowadays - ‘black wog’, or transmogrifying ‘black’ to the ’n-word’ - the American method of choice. The truth is, both the ‘b-word’ and its offspring the ’n-word’ do us no favours and neither should be used: both reduce, deny and trash our heritage. We shouldn’t be offering gifts to racists; we should be handing back what they gave us. ‘Bastard of African heritage’ does not carry any of the sting of ‘black bastard’ or the ’n-word’: instead it makes the racist have to work harder to insult us while still being forced to recognise that we have a heritage and are proud of it. Even if a racist were to persist with the British ‘black bastard’, it would be rendered redundant, futile, and the name-caller will have lost.

For those who aren’t yet proud: pride is taught, pride is learned, pride is built and pride comes from within. It’s time you tried it, because ‘black’ has got you and the rest of us nowhere. For those who point to the disrespect and worse that African Americans still suffer while self-labelling ‘African American’, the answer is that the problem is not that they embrace their African heritage: the problem is that America has a toxic, skin-obsessed, gun-obsessed, racist culture. Britain is not that bad yet, but don’t be fooled: it is by no means a benign multicultural paradise either; becoming another US is the direction of travel if we continue to encourage people already here and those arriving on our shores to label us in this racist way.

Institutional racism, trivialisation and infantilisation and the myth of self-identification

The “colour” of the skin - ‘black’ skin and ‘white' skin

And we shouldn’t be duped by being told it’s all about self-labelling - this is another myth, and another divide and rule tactic dreamt up by politicians and other so-called opinion-formers or influencers. The ONS is happy for people of African heritage to self-label, so long as the only labels on the menu are the divisive ones it prescribes, all of them starting with ‘black’ and disconnected from each other, and placed alongside ‘white’ as their supposed biological opposite, thereby perpetuating racism for ever more, much like it’s counterpart in America - the US Census Bureau - does. Now that’s institutional racism, if ever it existed, right there.

Trivialisation and infantilism of the social attitude problem perpetuates the racism, fosters over-simplistic solutions

Then there is the childish trivialisation; what I would call institutional trivialisation. I still remember as though it were yesterday the first time I heard about Dr Martin Luther King Jr. and his assassination. It was at a very young age in a school classroom lesson, when, at the end of that morning's lesson before the break for play, the teacher told us he was murdered “because of the colour of his skin”. I remember the teacher's name, how she looked, and the cadence with which she told us. And the way she told us and the simplistic way in which she did it, was perfectly appropriate for a class of children so young.

But it is not appropriate for adult discourse, be it spoken or written, particularly by people who purport to be otherwise intelligent or educated, nor by the organisations, some august, that some of these people represent. Dr King was not murdered “because of the colour of his skin”: he was pursued and murdered because of his heritage and the sense of entitlement the murderer and facilitators felt to re-enact the wholesale European American southern State belief that they had a God-given right to capture, enslave or kill people of African heritage without retribution. This was not just a belief: it was enshrined in laws and statutes exported from England to pre-independence America and consolidated in post-independence America up until the American Civil War. Even the UK’s so-called Equality Act of 2010, which supposedly passed scrutiny by both Houses of Parliament before being enacted, as all UK laws do, includes “colour” in its definition of racism and lists it first.7 This habitual infantilism, devaluation and reduction of people of African heritage to being nothing other than a misrepresented skin colour is what in fact perpetuates racism. It is morally corrupt and too many of us have been fooled by it.

This deliberate trivialisation of who we are is the same mindset that causes so-called Western politicians, aid agencies and media outlets to refer perpetually to 'developing countries' and ‘Third World’ countries. Those terms were in use 40 and 50 years ago when I was at school! The truth is, they don't really want those countries to emerge from those terms; they want them to be eternally ‘developing’.

A different set of rules applied to everyone else: Respect for heritage is deployed and people who should know better fail to question the discrepancy

And a similar deliberate and never articulated disjunction that enables people of European heritage to refer to people of South and East Asian heritage as what they are - Asian - thus respecting their continental ancestry, while ignoring it for people of the African diaspora is the same racist system of nomenclature that allowed Western powers to refer to themselves as 'First world countries' in contrast to 'Third world' while being careful never to utter the words 'Second world' to refer to the then Communist Eastern bloc European countries for whom the term was devised. One can suspect on good grounds that this is likely to be because of the extensive filial ties that exist between Eastern Europeans and many Americans, for example, since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The biggest determinant of, or threat to, a child's education and future prosperity is the educational level of the parents and whatever belief structure, aspirations and folklore they feed their children, l would argue. Therefore it is vital that we feed the right messages on racial origin and identity, and the truth and pride in that, to our children. It is from there that self-esteem, self-respect, confidence, respect for others in one's own community, and the physical and mental health and prosperity of that community grow. If all communities prosper within a multiracial society, then so does that society as a whole.

To conclude, the message is clear and it is this:

Racism is not about skin; it’s about heritage.

It is the notion that one population’s heritage, which includes its history, customs and language(s), and not just its physical appearance, is better than, or superior to, another’s. It’s a belief system, much like religion, where some populations think their religion is better than, or superior to, others. The only difference is that unlike religion, racism is not just practised in churches, mosques, temples and on the battlefield, but in pubs, bars, restaurants, schools and centres of higher education, workplaces, sports stadia and the street.

‘Black’ is not only heritage denial but a whole lot worse: it is the biggest act of identity theft in human history and the biggest act of theft our humanity.

This act of triple theft should be taken as seriously by the world and those countries that have made an industry of it as holocaust denial is taken.

The UN

The United Nations (UN) has come up with two initiatives in the past decade, albeit with the wrong title “of African descent” rather than ‘of African heritage’ but well-meaning nevertheless. However, the average person of African heritage, certainly in the UK, hasn’t heard of them, largely because they have been poorly publicised by the UN and have not been widely reported, if at all, by ‘Western’ media outlets. One was in 2011, which was designated The International Year for People of African Descent, with the following preamble:

“A Year Dedicated to People of African Descent

Around 200 million people who identify themselves as being of African descent live in the Americas. Many millions more live in other parts of the world, outside of the African continent. In proclaiming this International Year, the international community is recognising that people of African descent represent a distinct group whose human rights must be promoted and protected.”8

The second, which is ongoing and is in it’s seventh year, yet, again for reasons already cited, is under the radar in the public consciousness both here and abroad, is the UN’s International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024), which has this as its mission statement:

“As proclaimed by the General Assembly, the theme for the International Decade is “People of African descent: recognition, justice and development.””9

and statements like this:

“More than four million slaves were shipped to Brazil from the coast of Africa during the 16th century and onward.”9

And that’s all very well. But it’s not enough for us to sit and wait for transnational or national governments and organisations to get round to championing our cause. Far too many of us do this. We have to get up off our backsides, take the bull by the horns, lead on this by example - by refusing and rejecting ‘black’ and insisting on what we actually are - people of African heritage. Thereby we lead ourselves out of the darkness, and the trivialisation and denigration of our heritage as nothing but ‘darkness’, and thereby we lead ourselves out of the social quagmire that we have been languishing in for so long in these modern times.

The likes of the legendary former footballer Pele in Brazil are not “black Brazilians” but Brazilians of African heritage.

What is killing us is not just racist European American police officers, or the occasional British European police officer here, or, in large numbers at once during the apartheid era, South African police officers of European (mostly Dutch) heritage, or civil wars on African soil sustained by weapons, politicians and mercenaries of European origin, but ignorance about our collective selves, denigration and suppression by many of European heritage, including historians, of positive facts as to our collective African history and our contribution to world civilisation, coupled with a dissemination of the notion that our lives are of a lower value, all unwittingly honed and enhanced by us and passed down from one generation to the next, along with a toxic self-hatred and an attempt to run away from and deny our African heritage that has developed among a significant contingent of us. This attempt to flee one’s continental ancestry has, historically, been far more of a problem amongst British, French and Dutch African-Caribbeans than with African-Americans, African-Brazilians, African-Colombians and African-Cubans, for example.

Dutch people of African heritage

That said, the English-language Dutch publication Brill published an article in 2014, showing that this was changing for the better in the Netherlands,10 compared with earlier generations, though anecdotally exceptions can, of course, be found. Some of the change in attitudes seems to have been driven by popular culture, e.g. the rise of Afrobeat on the music scene, and the increasing presence of Continentals (continental Africans) in top-flight football teams in Europe.

UK nationals of African heritage

The same is true in the UK, although, I would argue, less perceptibly so and not fast enough nationally, though in London especially, divisions have noticeably eased as the lines of distinction have blurred through the extensive social mixing and intermarriage among young people I mentioned earlier, which wasn’t common even as recently as the 1980s. The research study and paper, We all Black innit,11 (“We are all black, isn’t it?” [“We are all black, aren’t we?”]) published by L.Owusu-Kwarteng at the University of Greenwich in London in 2017 bears out the anecdotal and experiential observations I have made. However, the ONS still insists on trying to maintain these divisions in its ubiquitous ‘ethnic monitoring questionnaires’ that all schools, universities and employers are obliged to use and in Censuses right up to and including this year’s.

French nationals of African heritage

In the case of France, the Négritude writings of the 1930s to 1960s had a cohesive effect on the African heritage population (Continental and African-Caribbean populations) there. When this literary movement faded after African countries gained their independence while the ‘French Antilles’ remained possessions of and part of France in the form of départements, so a divide appeared for a time between the African and African-Caribbean populations in France, the latter perforce being ‘French people’. Now the picture is less clear, as French society has been more preoccupied with the threat to social order and national unity in that country posed by islamic terrorism.

Autogenocide and the label given

When crime, as it does, occurs between people of African heritage (predominantly men and boys) in cities in the US and UK over the trivial, and petty disputes, and perceived “dissing” (disrespect) and misplaced and mis-directed machismo, and, in some cases, drug-dealing and ‘territory’, it is compounded by being given the ignorant and ridiculous, packaged, abbreviated label “black-on-black crime” by police in the US, copied by the police in the UK, and in both cases, copied by some people of African heritage.

‘Black’ and ‘woke’!

To those who claim they’re ‘woke’, i.e. awake to the layers of, the machinations and sophistry behind, the historical backdrop to, and the political, geopolitical, economic and societal forces that underlie racism and structural racism, I say this: you cannot be truly ‘woke’ while still calling yourself, and allowing people to call you, a “black person”; you cannot decry racial injustice of the kind people of African heritage suffer while still accepting and defining yourself by this racist label. The two are mutually incompatible. To say otherwise is a failure of insight, a blindness to fact, and ultimately an act of self-delusion. The true awakening comes when you come to realise this.

So let us, finally, once and for all, return ‘black’ to the descriptive uses for which it was originally intended - to describe animals, inanimate objects, mood states and events - and lay to rest, once and for all, the corrupted meaning that was first applied to human beings by racist kidnappers, human traffickers, enslavers, torturers and rapists between 1440 and 1888. RIP

Dr Allswell E. Eno

7th April 2021

References:

1. Kennedy, R. (2002, 2003). Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word. New York: Vintage Books

2.

Sluiter, E. (1997). New Light on the “20. And Odd Negroes” Arriving in Virginia, August 1619. The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol.54, No.2

3.

Tsri, K. (2016). Africans are not black: A case for conceptual liberation. 1st Edition. Abdingdon; New York: Routledge

4.

Shapiro, F. (2016). The origin of “African American”. Yale Alumni Magazine

5.

Anonymous, (1782). Sermon On the Capture of Lord Cornwallis. By an African American. Philadelphia

6.

United Kingdom (2021). Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities: The Report. Assets Publishing Service

7.

United Kingdom (2010). The Equality Act 2010. Ch.1, Section 9. London: The Stationery Office

8.

Geneva (2011). 2011, International Year for People of African Descent. United Nations General Assembly, United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

9.

Geneva (2015). International Decade for People of African Descent. United Nations General Assembly, United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

10.

de Witte, M. (2014). Heritage, Blackness and Afro-Cool. Styling Africanness in Amsterdam. African Diaspora, Vol. 7, Issue 2; Leiden: Brill

11.

Owusu-Kwarteng, L. (2017). We all Black innit? Analysing intra-ethnic relations between Black African and African Caribbean groups in Britain. Greenwich Academic Literature Archive

© Allswell E. Eno